I think the season might have changed from spring to summer while I wasn’t looking. A quiet breath of change that happened maybe while I was grading. Or shearing. Or mourning.

Collectively, a lot of us are mourning right now. Lives lost to COVID. Lives lost to violence. Lost experiences. Lost sense of normalcy. The world, I think, is undergoing some changes, and it can be hard to keep up or know quite where you fit.

I’m feeling all of that.

I set out at the beginning of quarantine with grand intentions to write more, but I’ve struggled with it. The more you don’t write, the harder it is to get back in the habit; it’s a skill that must be practiced as much (maybe more) than it is a talent. Early on, it was the chaos of online teaching that made me feel stuck. I only had so much brain space, and it didn’t seem I could fit much else in beyond my classroom. Then it was loss and depression and anxiety. Personal and collective.

We’re all going through a collective experience of trauma right now. Several of them really. Some people are handling it better than others, I think. Some people are really struggling. Some people don’t quite know what to feel.

Suddenly, and collectively, we’ve come to the ever present but often ignored conclusion that our lives are very often out of our control.

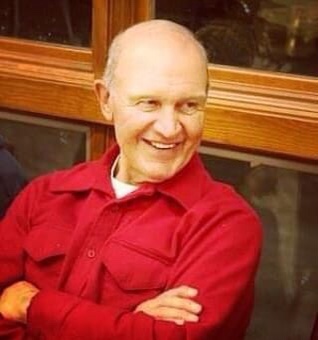

Beyond our collective grief and mourning, my family has experienced personal loss. My grandpa passed away this spring, an illness or injury that it seemed like the doctors couldn’t quite pin down took him from us. Thanks to the virus, most of us didn’t really get to say goodbye. We texted and called. We posted memories and remembrances on social media. We even had a collective ice cream social on Zoom. (If you knew my grandpa, you know that he loved ice cream.)

We didn’t get to hug him or each other, though. We didn’t get to have a wake or a funeral.

I’m sure I’m not the only member of the family who felt depression hang over me like a shadow as he faded from us. The virus creates loss without context. An emptiness that just seems to appear in front of you like a fall into Wonderland through a rabbit hole.

(Hmmm…I think grandpa would like that analogy; he was a nationally known rabbit breeder, and it seems very likely to me that he would have been pretty comfortable with his gateway to the afterlife taking the shape of a rabbit hole or maybe a path through a rabbit coop full of his favorite Flemish Giants.)

My depression had been waiting in the wings since the start of the virus, and it poured onto center stage following on the heels of our loss. It does that. Comes and goes, but never really goes. It was my companion for a few weeks, a welling up inside me that occasionally rose to prominence and took over. I was thankful for my support system. For my friends who called or texted to check in. For family, who knew my loss by feel because it had spread across their skin and hearts as well. For my guy, who didn’t have the words (because, believe me, no one ever does) but who wrapped me up in his arms and told me he would be right there as long as I needed him, who let me cry on his shoulder and brought me pizza when food had lost a lot of its appeal.

I’ve read that grief is love that has no where to go, that that’s why we should let people have their grief, to ride through the rough terrain of loss rather than try to smooth it over for them with platitudes. You have to learn to ride through the rough road carrying the love with you; no one can navigate the holy pain of loss in your stead.

One of my aunts wrote a touching tribute to grandpa a few days before his death, when we all knew it was coming and felt ourselves waiting for the hand of the creator to deliver him from his intense pain. She wrote about all the things she would miss. All the ways she would miss him.

I somehow didn’t see her reflection until a few days after he passed. I had spent the in between thinking about all the things I would miss as well.

One line she wrote, “I will miss the way you measured time by season and weather, the way any farmer does,” bounced around in my chest, filling space in an empty spot that I hadn’t known was there.

I do that too…

My grandfather left an obvious legacy. He and my grandmother raised nine children on a farm along the rock river. Those children, in turn, raised their children in their own way–some on farms of their own; some, like mine, in town in a small house with a white picket fence–but all of us have a little plow dirt in our blood I think, some more obviously than others. Most of us have a dose of Midwestern common sense. Many of us know the magic of being rooted, connected to the growth of things in a very visceral way. He quietly taught us that, I think.

Not long after he passed, the month of May surprised Central Illinois with a late frost. Dad came over and helped me cover my garden. We spread plastic sheets over green beans and put buckets upside down over tomatillos and tomatoes. I used actual blankets to tuck in my broccoli and slung Max’s first coat over my lettuce to protect it, as I had with him, from the cold. I thought about Grandpa a lot that night, wondering how many times he worked to protect the crops from a late frost, thought about the way he taught dad how to drive a tractor and plant corn in rows and the way Dad taught me.

The frost claimed no casualties in my garden, despite rolling over the ridge line low and fierce; it was protected by the knowledge that a family passes from one to the next.

It strikes me sometimes that he isn’t here anymore; that I won’t see him on Christmas Eve. That we won’t talk about my horses again; I won’t see him nod approvingly and tell me “that’s a fine looking horse” with the knowledge of a seasoned horseman when I pull out a photo of my latest project. I won’t hear him comment on the price of milk or this year’s corn crop or the weather. He won’t wrap me up in a bear hug that smells just a little like a barn. (His hugs would lift us off the ground until he was well into his 70s.)

I will miss him.

But I will think of him when I see the sun set over corn fields. When I start up a tractor. When I breathe in the scent of freshly plowed garden dirt. When I eat ice cream, like he did, with a fork.

I suspect that I will measure “time by season and weather” for the rest of my days, the same way he did through all of his.

I think it’s true that grief is love with no where to go. I’ve learned that the process of grieving teaches you where to put that love, how to share it, how to pull it out when you need to remember the ways it made you who you are.

I hope your grieving, however it looks now, teaches you more about love and reminds you how to be full.